Delivered in a presentation meeting by Hosnul Wahid at Ijen-Geopark Bondowoso office.

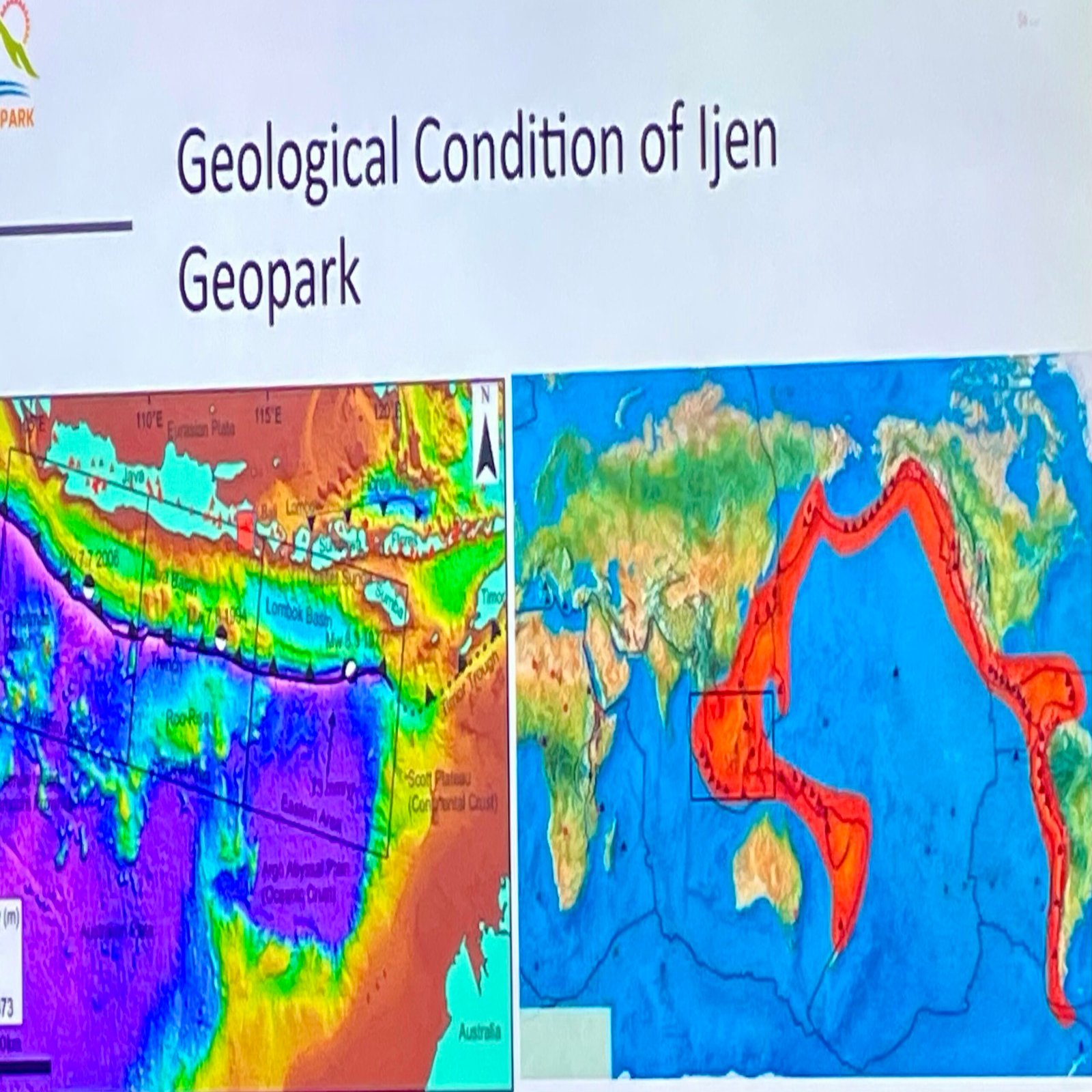

Roughly 30 million years ago, deep beneath what is now East Java, the earth began to move.

The tectonic plates — those massive slabs of the earth’s crust — slowly collided and pushed against each other. Some plates were thick and heavy, others thin and flexible. When they met, the heavier plates were forced downward, sliding beneath the lighter ones.

As these movements continued, the pressure and heat deep underground built up, and the molten rock — magma — began to seek a way to escape.

That movement, that ancient pressure, was the birth of volcanoes.

The Ancient Volcanoes of Southern Java

If we look back to those times, many of Java’s earliest volcanoes formed along its southern coast — ancient giants that are now long extinct. Over millions of years, wind, rain, and sea waves eroded their peaks. What remains today are fossilized mountains, or what geologists call paleovolcanoes.

One example is Meru Betiri, whose eroded form still hints at its volcanic past.

The magma supply beneath it eventually shifted elsewhere, leaving behind only weathered stone — the skeletal remains of a volcano that once towered high above the sea.

When the Magma Moved

The shifting of tectonic plates didn’t stop.

As the subduction zone (where plates dive beneath one another) gradually moved northward, the “magma pipes” — channels that carried molten rock to the surface — also changed direction.

Old volcanoes went silent, while new ones rose further inland.

That’s how the chain of volcanoes across Java slowly migrated toward the center of the island.

And in Bondowoso, this process gave birth to one of the most remarkable geological structures in Indonesia — the Ancient Ijen Caldera (Ijen Purba).

A Supervolcano in East Java

Much like Toba, Rinjani, or Bromo, the Ancient Ijen Volcano was once a colossal mountain — a vast volcanic complex shaped like a giant bowl, or caldera, from the Italian word for “cauldron.”

When its magma chamber was full, eruptions were immense, fueled by enormous underground pressure.

Then, around 100,000 years ago, came a cataclysmic explosion.

The eruption was so powerful that the volcano’s summit collapsed into itself, leaving behind a vast hollow — the Ijen Caldera we know today.

Traces of Volcano

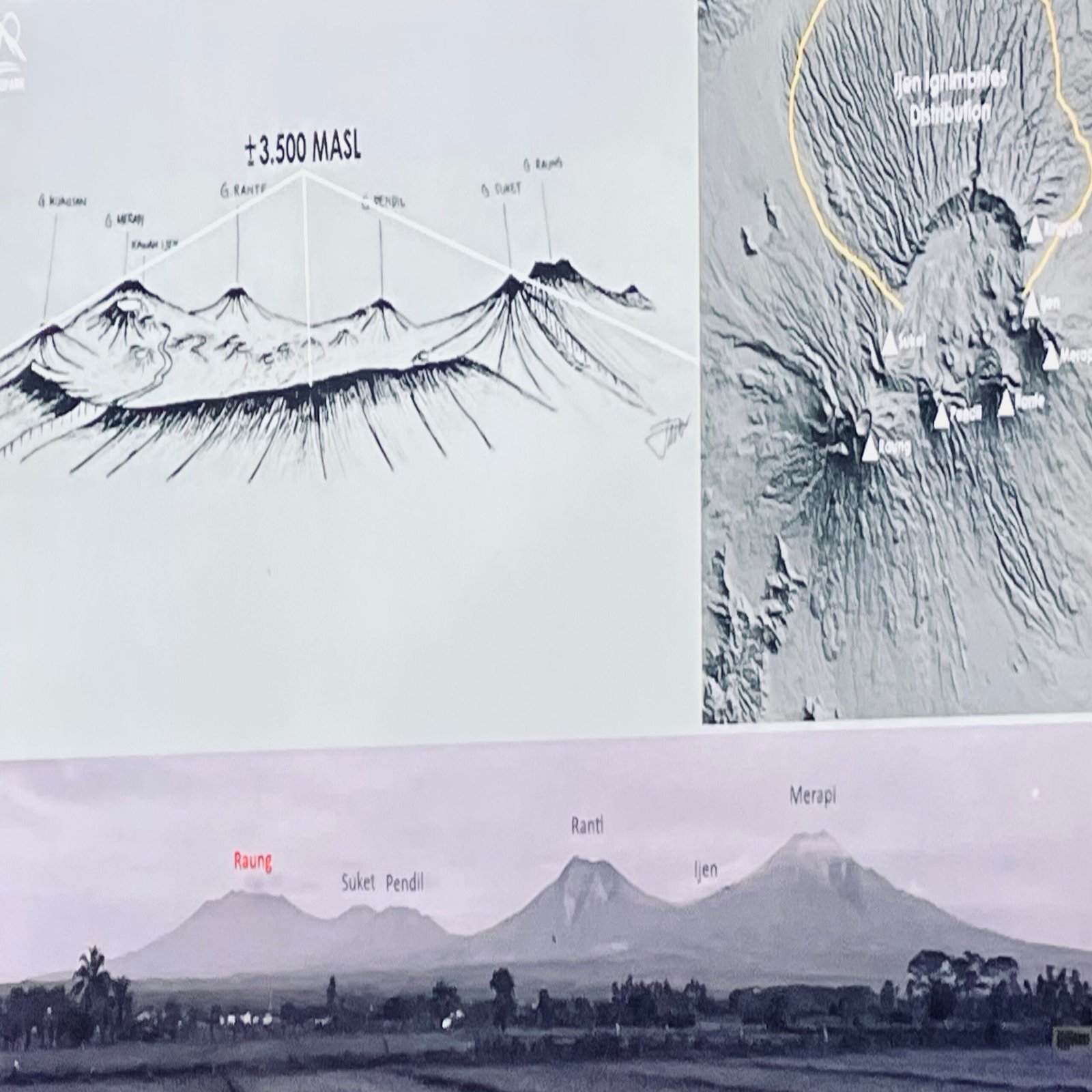

From the northern caldera wall of Megasari, you can still see the remnants of that ancient volcano — a structure that once spanned 18 kilometers in diameter and 12 kilometers across.

Researchers such as Dr. Firman from the Bandung Institute of Technology (ITB) have studied these volcanic remnants extensively. Their findings suggest that the Ancient Ijen Volcano once stood over 3,500 to 4,000 meters high — possibly taller than today’s Raung or Semeru.

Imagine that: a mountain once higher than 4,000 meters, blown apart and reduced to a basin nearly a kilometer deep. Its eruptions sent volcanic material drifting northward, blanketing the lowlands of Situbondo, Prajekan, Cermee, and Asembagus. That’s why, even today, those regions are filled with rocky, hardened terrain — silent witnesses to the fury of Ijen’s ancient past.

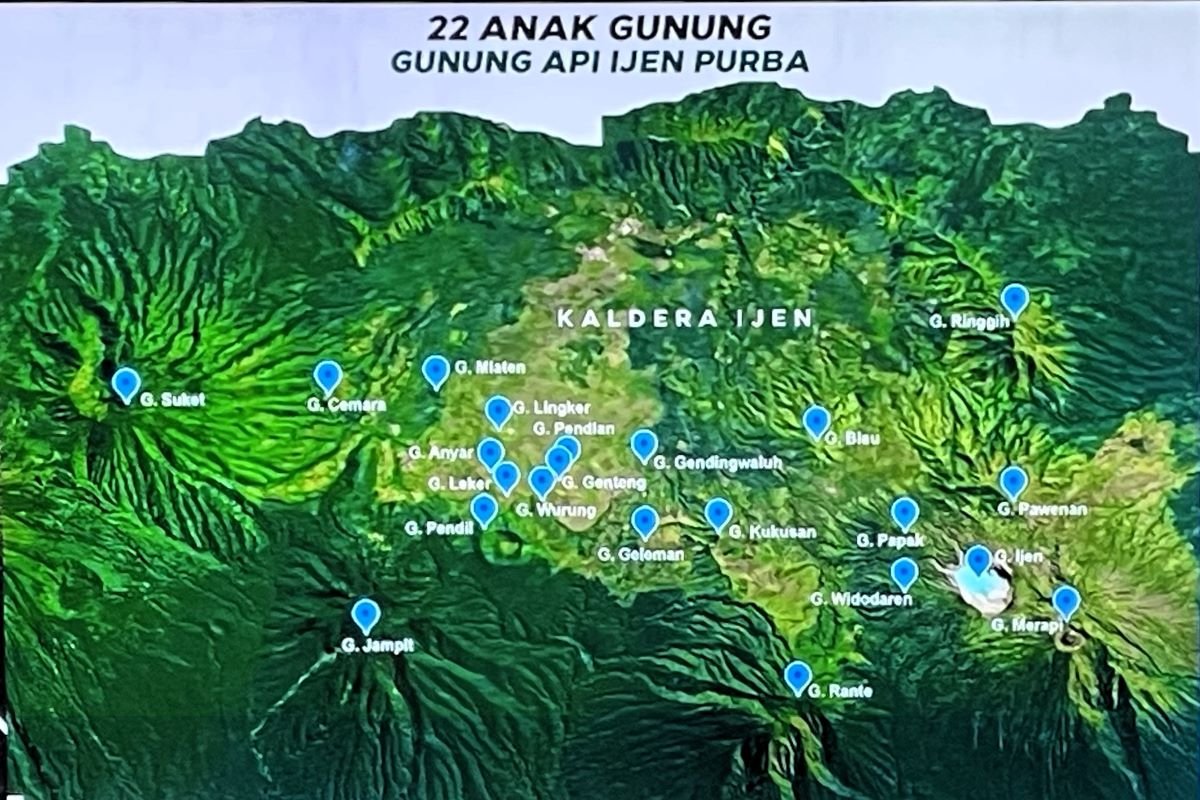

The Birth of Twenty-Two New Peaks

After the great collapse, the caldera did not fall silent.

Over time, smaller eruptions — both explosive and effusive — created new volcanic cones within and around the ancient basin.

From this rebirth, 22 new volcanic peaks emerged. *

Mountains like Suket, Pendil, Ranti, and Kawah Wurung are all part of this second generation — gifts from the earth after its great transformation.

“It’s as if nature gave us two gifts — first, the magnificent caldera, and then, new mountains rising within it.”

The Living Volcanoes: Ijen and Raung

Today, two active volcanoes — Mount Ijen and Mount Raung — continue to shape the landscape of Bondowoso and Banyuwangi. Both share the same magma source, connected through deep subterranean channels.

Their ongoing activity is a sign of a living earth, not a threat to fear.

“Don’t worry when the volcano rumbles,” Wahid said with a smile. “Be worried when it doesn’t. Because silence means the magma is trapped.”

The occasional tremor or plume of smoke reminds us that beneath the surface, the planet is still breathing.

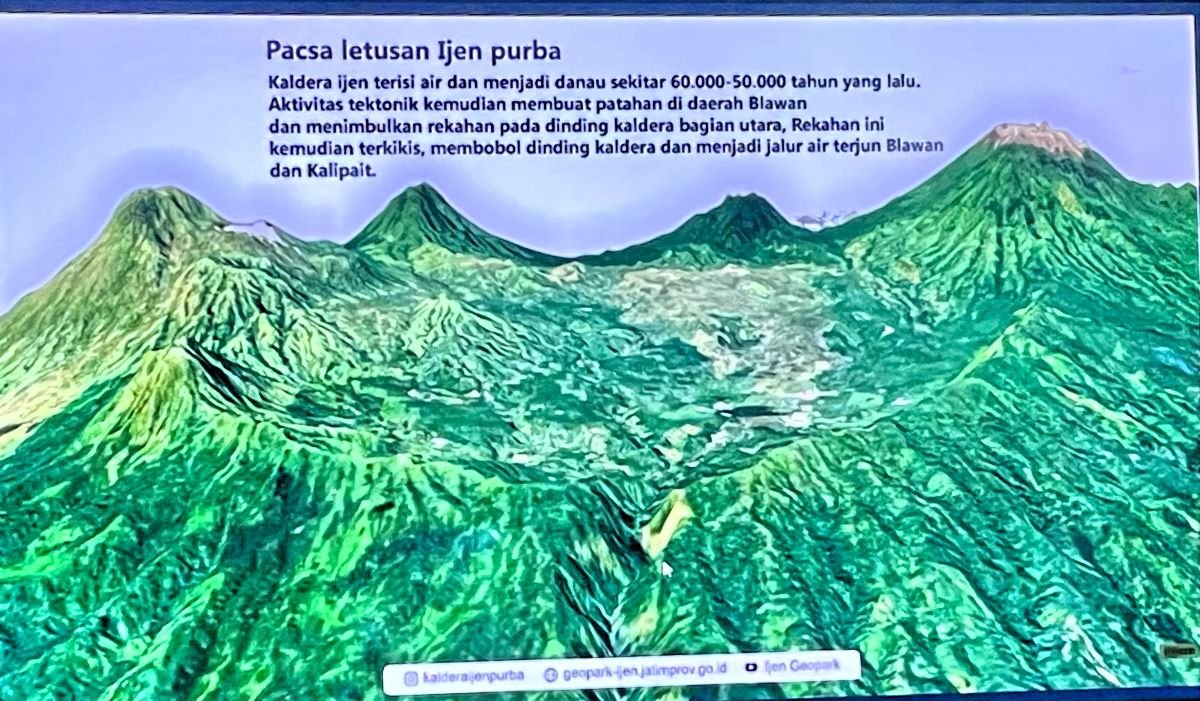

Cracks, Faults, and Waterfalls

Beyond the caldera’s rim, fault lines — or Sesar (geology) — also mark Ijen’s dynamic history.

One of the most visible examples can be found near Blawan Waterfall, where the cliffside splits dramatically, showing evidence of tectonic movement and erosion.

These faults channel hot springs and underground rivers, making Blawan one of the richest sources of geothermal water in East Java. Rainwater seeps into the ground at higher elevations, absorbed by volcanic rock, and re-emerges as natural hot springs — clear evidence that the earth beneath Ijen remains active and alive.

The Beauty Left Behind by Fire

Volcanic eruptions, though often catastrophic in the moment, have sculpted some of the world’s most stunning landscapes. Ijen’s story is no different. From the ashes of ancient eruptions came fertile soil, flowing rivers, and new ecosystems.

What once was a site of devastation is now a cradle of biodiversity and life — a place where science, culture, and beauty intertwine.

To be continued — The Ancient Lake and the Fiery Birth of Ijen (Part 3)